Prof. Nick Feamster’s Research Drives Wall Street Journal Investigation of Streaming Video

Over three-quarters of today’s internet traffic comes from streaming video, a number that is only projected to rise over time. To meet this demand, internet service providers offer consumers faster data speeds at premium prices, with gigabit-per-second tiers available in some areas. But do these pricier plans actually improve the quality of video streaming? A Wall Street Journal investigation, published August 20th, answered this question with the help of UChicago Professor Nick Feamster, in a collaboration that both informs consumers and advances science.

The story, “The Truth About Faster Internet: It’s Not Worth It,” began three years ago with what the reporters thought would be a simple question: do faster speeds matter for streaming video? To answer it, they turned to Feamster, then at Princeton University, for his expertise on networked computer systems. Feamster’s group had developed software systems that could reliably measure the actual internet speeds consumers received at home, one important part of the WSJ inquiry. But gathering the other half of the data — the performance of streaming video services in those homes — would require a mix of systems, machine learning, and recruitment.

While video providers such as Netflix, Amazon, and YouTube can collect data on the quality that users receive through their software, ISPs and outside researchers are in the dark. With the help of the Wall Street Journal, the researchers recruited more than 60 households, collected information about their internet service, and installed a monitor of the data passing through their network. But challenges remained.

“We're basically looking at nonsense traffic; it's all encrypted, we can't see the contents of any of it, and we somehow want to know: Is the user streaming a Netflix video, and if so, what's the resolution? And, how long did it take to start playing?,” said Feamster, Neubauer Professor of Computer Science and Faculty Director of the Center for Data and Computing. “That's an interesting and very challenging machine learning inference problem. We see a bunch of encrypted data, and we’re trying to figure out the quality of this video—not just ‘speed’, but the quality of the user’s actual experience.”

The work led to a research paper and a new tool called Net Microscope, which infers video streaming quality metrics such as startup delay and resolution in real time from the encrypted data stream. By gathering data from more than 200,000 video sessions from the volunteer homes, the team trained a model that that can look at encrypted data and identify which streams are from Netflix, YouTube, Amazon, and Twitch, as well as the quality that end users experience.

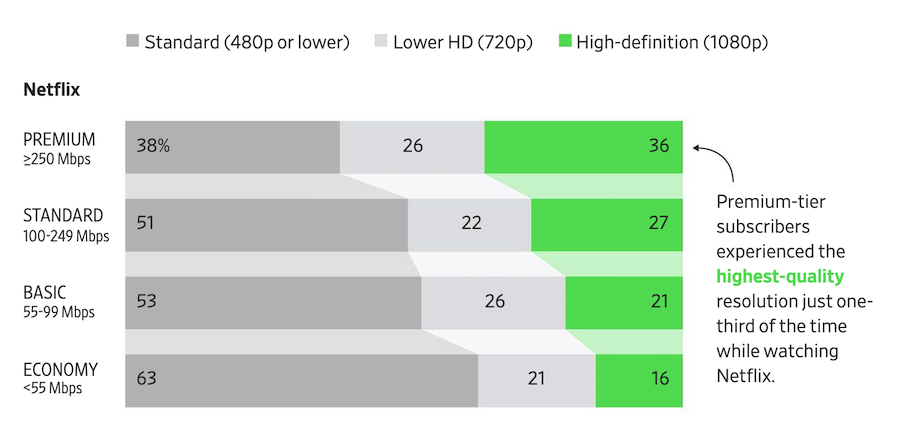

From there, the researchers could finally answer the question posed by the Wall Street Journal: How do these services perform at different internet speeds? The study found that streaming video performance plateaus long before the upper tier plans offered by ISPs, with plans above 100 megabits-per-second only marginally improving startup delays and resolution, even when multiple devices are viewing videos simultaneously.

That’s valuable information for consumers, who might feel compelled to upgrade to a more expensive plan if they’re unsatisfied with their streaming video quality at home. But it’s also useful information for ISPs, Feamster said, who can better help their customers find the true cause of unsatisfactory performance instead of just recommending faster service.

“Anything we do that can help basically shed more light into that question from consumers can also ultimately help the operation of the network itself,” Feamster said. “So it kind of goes both ways.”

The project fits Feamster’s broader research focus on the performance and security of communications networks, which encompasses work on Internet of Things technologies, censorship and information control over online platforms, and policy questions such as net neutrality and broadband access. Like the Wall Street Journal project, many of these research areas and policy issues require creating new software and systems that can collect data and measure performance in the real world. From the lens of his new role at the Center for Data and Computing, Feamster sees this project as the beginning of what he hopes will be more work at the intersection of data science, public policy and investigative journalism.

“Addressing policy problems depends on having access to good data, because what is needed to inform the debate is accurate information about what's actually going on,” Feamster said. “These datasets generally don't exist, there's no tranche of speed test data that gets dropped in our lap that could answer these questions. We have to design the method and build the system to gather data that nobody else has…then we can provide an answer.”